Let’s continue our journey to learn the MVVM pattern and how to apply it to develop a Universal Windows app. In this post we’re going to explore some advanced scenarios which are frequent when you develop a real project: how to handle secondary events, how to exchange message and how to use the dispatcher.

Handling additional events with commands

In the previous posts we’ve learned how all the XAML controls that allow user interaction, like a button, offer a property called Command, which we can use to connect an event to a method without using an event handler. However, the Command property can be used to handle only the main interaction event exposed by the control. For example, if you’re working with a Button control, you can use a command to handle the Click event. However, there are many scenarios where you need to handle secondary events. For example, the ListView control exposes an event called SelectionChanged, which is triggered when the user selects an item from the list. Or the Page class exposes a Loaded event that is triggered when the page is loaded.

To handle these situations we can leverage the Behaviors SDK, which is a library from Microsoft (recently turned into an open source project on GitHub) that contains a set of behaviors ready to be used in your apps. Behaviors are one of the most interesting XAML features, since they allow to encapsulate some logic, which typically should be handled in code behind, in components that can be reused directly in XAML. Behaviors are widely used in MVVM apps, since they help to reduce the code we need to write in the code behind classes.

A behavior is based on:

- A Trigger, which is the action that will cause the behavior’s execution.

- An Action, which is the action to perform when the behavior is executed.

The Behaviors SDK includes a set of triggers and actions which are specific to handle our scenario: connecting secondary events to commands defined in the ViewModel.

Let’s see a real example. The first step is to add the Behaviors SDK to your project. If you’re working on a Windows / Windows Phone / WPF / Silverlight project, the SDK is included in Visual Studio and it’s available in the Extensions section of the Add reference menu. Otherwise, if you’re working on a Windows 10 app, there’s a new version of the SDK which is available as a NuGet package, like any other library, and that can be updated independently from Visual Studio and the Windows 10 SDK. To install it, it’s enough to right click on your project, choose Manage NuGet Packages and install the pacakge identified by the id Microsoft.Xaml.Behaviors.Uwp.Managed if it’s a C# / VB.NET application or Microsoft.Xaml.Behaviors.Uwp.Native if it’s a C++ application.

The next step is to declare, in the XAML page, the namespaces of the SDK, which are required to use the behaviors: Microsoft.Xaml.Interactivity and Microsoft.Xaml.Interactions.Code, like in the following sample.

<Page

x:Class="MVVMLight.Advanced.Views.MainView"

xmlns:interactivity="using:Microsoft.Xaml.Interactivity"

xmlns:core="using:Microsoft.Xaml.Interactions.Core"

mc:Ignorable="d">

</Page>

Thanks to these namespaces, you’ll be able to use the following classes:

- EventTriggerBehavior, which is the behavior that we can use to connect a trigger to any event exposed by a control.

- InvokeCommandAction, which is the action that we can use to connect a command defined in the ViewModel with the event handled by the trigger.

Here is how we apply them to handle the selection of an item in a list:

<ListView ItemsSource="{Binding Path=News}"

SelectedItem="{Binding Path=SelectedFeedItem, Mode=TwoWay}">

<interactivity:Interaction.Behaviors>

<core:EventTriggerBehavior EventName="SelectionChanged">

<core:InvokeCommandAction Command="{Binding Path=ItemSelectedCommand}" />

</core:EventTriggerBehavior>

</interactivity:Interaction.Behaviors>

</ListView>

The behavior is declared like if it’s a complex property of the control and, as such, it’s included between the beginning and ending tag of the control itself (in this case, between <ListView> and </ListView>). The behavior’s declaration is included inside a collection called Interaction.Behaviors, which is part of the Microsoft.Xaml.Interactivity namespace. It’s a collection since you can apply more than one behavior to the same control. In this case, we’re adding the EventTriggerBehavior mentioned before which requires, by using the EventName property, the name of the control’s event we want to handle. In this case, we want to manage the selection of an item in the list, so we link this property to the event called SelectionChanged.

Now that the behavior is linked to the event, we can declare which action we want to perform when the event is triggered. We can do it by leveraging the InvokeCommandActionClass, which exposes a Command property that we can link, using binding, to an ICommand property in the ViewModel.

The task is now completed: when the user will select an item from the list, the command called ItemSelectedCommand will be invoked. From a ViewModel point of view, there aren’t any difference between a standard command and a command connected to a behavior, as you can see in the following sample:

private RelayCommand _itemSelectedCommand;

public RelayCommand ItemSelectedCommand

{

get

{

if (_itemSelectedCommand == null)

{

_itemSelectedCommand = new RelayCommand(() =>

{

Debug.WriteLine(SelectedFeedItem.Title);

});

}

return _itemSelectedCommand;

}

}

This command takes care of displaying, in the Ouput Windows of Visual Studio (using the Debug.WriteLine() method), the title of the selected item. SelectedFeedItem is another property of the ViewModel which is connected, using binding, to the SelectedItem property of the ListView control. This way, the property will always store a reference to the item selected by the user in the list.

Messages

Another common requirement when you develop a complex app is to find a way to handle the communication between two classes that don’t have anything in common, like two ViewModels or a ViewModel and a code-behind class. Let’s say that, after something happened in a ViewModel, you want to trigger an animation in the View: in this case, the code that will perform it will be stored in the code-behind class, since we’re still talking about code that is related to the user interface.

In these scenarios, the strength of the MVVM pattern (which is a clear separation between the layers) can also become a weakness: how can we handle the communication between the View and ViewModel since they don’t have anything in common, exept for the second being set as DataContext of the first? These situations can be solved by using messages, which are packages that a centralized class can dispatch to the various classes of the application. The most important strength of these packages is that they are completely disconnected: there’s no relationship between the sender and the receiver. By using this approach:

- The sender (a ViewModel or a View) sends a message, specifying which is its type.

- The receiver (another ViewModel or View) subscribes itself to receive messages which belongs to a specific type.

In the end, a sender is able to send a message without knowing in advance who is going to receive it. Viceversa, the receiver is able to receive messages without knowing the sender. Every MVVM toolkit and framework typically offers a way to handle messages. MVVM Light makes no exceptions; we’re going to use the Messenger class to implement the sample I’ve previously described: starting an animation defined in the code behind from a ViewModel.

The message

The first step is to create the message we want to send from one class to the other. A message is just a simple class: let’s create a folder called Messages (it’s an optional step, it’s just to keep the structure of the project clean) and let’s right click on it in Visual Studio and choose Add –> New item –> Class. Here is how our message looks like:

public class StartAnimationMessage

{

}

As you can see, it’s just a class. In our case it’s empty, since we juts need to trigger an action. It can also have one or more properties in case, other than triggering an action, you need also to send some data from one class to the other.

The sender

Let’s see now how our ViewModel can send the message we’ve just defined. We can do it by using the Messenger class, included in the namespace GalaSoft.MvvmLight.Messaging. In our sample, we assume that the animation will be triggered when the user presses a button. Consequently, we use the Messenger class inside a command, like in the following sample:

private RelayCommand _startAnimationCommand;

public RelayCommand StartAnimationCommand

{

get

{

if (_startAnimationCommand == null)

{

_startAnimationCommand = new RelayCommand(() =>

{

Messenger.Default.Send<StartAnimationMessage>(new StartAnimationMessage());

});

}

return _startAnimationCommand;

}

}

Sending a message is quite easy. We use the Default property of the Messenger class to get access to the static instance of the messenger. Why static? Because, to properly work, it needs to be the same instance for the entire application, otherwise it won’t be able to dispatch and receive messages coming from different classes. To send a message we use the Send<T>() method, where T is the type of message we want to send. As parameter, we need to pass a new instance of the class we have previously created to define a message: in our sample, it’s the StartAnimationMessage one.

Now the message has been sent and it’s ready to be received by another class.

The receiver

The first step, before talking about how to receive a message, is to define in the XAML page the animation we want to trigger when the button is pressed, by using the Storyboard class:

<Page

x:Class="MVVMLight.Messages.Views.MainView"

xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation"

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml"

xmlns:local="using:MVVMLight.Messages.Views"

xmlns:d="http://schemas.microsoft.com/expression/blend/2008"

xmlns:mc="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/markup-compatibility/2006"

DataContext="{Binding Source={StaticResource ViewModelLocator}, Path=Main}"

mc:Ignorable="d">

<Page.Resources>

<Storyboard x:Name="RectangleAnimation">

<DoubleAnimation Storyboard.TargetName="RectangleTranslate"

Storyboard.TargetProperty="X"

From="0"

To="200"

Duration="00:00:05" />

</Storyboard>

</Page.Resources>

<Grid Background="{ThemeResource ApplicationPageBackgroundThemeBrush}">

<Rectangle Width="100" Height="100" Fill="Blue">

<Rectangle.RenderTransform>

<TranslateTransform x:Name="RectangleTranslate" />

</Rectangle.RenderTransform>

</Rectangle>

</Grid>

<Page.BottomAppBar>

<CommandBar>

<CommandBar.PrimaryCommands>

<AppBarButton Label="Play" Icon="Play" Command="{Binding Path=StartAnimationCommand}" />

</CommandBar.PrimaryCommands>

</CommandBar>

</Page.BottomAppBar>

</Page>

We have included in the page a Rectangle control and we have applied a TranslateTransform. It’s one of the transformations included in the XAML, which we can use to move a control in the page simply by changing its coordinates on the X and Y axis. The animation we’re going to create will be applied to this transformation and it will change the control’s coordinates.

The animation is defined using a Storyboard as a resource of the page: its type is DoubleAnimation, since it will change a property (the X coordinate of the TranslateTransform) which is represented by a number. The animation will move the rectangle from the coordinate 0 (the From property) to the coordinate 200 (the To property) in 5 seconds (the Duration property). To start this animation, we need to write some code in the code behind: in fact, we have to call the Begin() method of the Storyboardy control and, since it’s a page resource, we can’t access it directly from our ViewModel.

And here comes our problem: the animation can be started only in code behind, but the event that triggers it is raised by a command in the ViewModel. Thanks to our message, we can easily solve it: it’s enough to register the code behind class as receiver of the StartAnimationMessage object we’ve sent from the ViewModel. To do it we use again the Messenger class and its Default instance:

public sealed partial class MainView : Page

{

public MainView()

{

this.InitializeComponent();

Messenger.Default.Register<StartAnimationMessage>(this, message =>

{

RectangleAnimation.Begin();

});

}

}

In the constructor of the page we use, this time, the Register<T>() method to turn the code behind class into a receiver. Also in this case, as T, we specify the type of message we want to receive; every other message’s type will be ignored. Moreover, the method requires two parameters:

- The first one is a reference to the class that will handle the message. In most of the cases, it’s the same class where we’re writing the code, so we simply use the this keyword.

- An Action, which defines the code to execute when the message is received. As you can see in the sample (defined with an anonymous method) we get also a reference to the message object, so we can easily access to its properties if we have defined one or more of them to store some data. However, this isn’t our case: we just call the Begin() method of our Storyboard.

Our job is done: now if we launch the application and we press the button, the ViewModel will broadcast a StartAnimationMessage package. However, since only the code behind class of our main page subscribed to it, it will be the only one to receive it and to be able to handle it.

Be careful!

When you work with messages, it’s important to remember that you may have configured your application to keep some pages in cache. This means that if we have configured a ViewModel or a code behind class to receive one or more messages, they may be albe to receive them even if they’re not visible at the moment. This can lead to some concurrency problems: the message we have sent may be received by a different class than the one we expect.

For this reason, the Messenger class offers a method called Unsubscribe<T>() to stop receiving messages which type is T. Typically, when you need to intercept messages in a code behind class, you need to remember to call it in the OnNavigatedFrom() event, so that when the user leaves the page it will stop receiving messages.

protected override void OnNavigatedFrom(NavigationEventArgs e)

{

Messenger.Default.Unregister<StartAnimationMessage>(this);

}

For the same reason, it’s also better to move the Register<T>() method from the constructor to the OnNavigatedTo() method of the page, to make sure that when the user navigates again to the page it will be able to receive messages again.

Working with threads

The user interface of Universal Windows app is managed by a single thread, called UI Thread. It’s critical to keep this thread as free as possible; if we start to perform too many operations on it, the user interface will start to be unresponsive and slow to use. However, at some point, we may need to access to this thread; for example, because we need to display the result of an operation in a control placed in the page. For this reason, most of the Universal Windows Platform APIs are implemented using the async / await pattern, which makes sure that long running operations aren’t performed on the UI thread, leaving it empty to process the user interface and the user interactions. At the same time, the result is automatically returned on the UI thread, so it’s immediately ready to be used by any control in the page.

However, there are some scenario where this dispatching isn’t done automatically. Let’s take, as example, the Geolocator API, which is provided by the Universal Windows Platform to detect the location of the user. If you need to continuosly track the user’s position, the class offers an event called PositionChanged, which you can subscribe with an event handler to get all the information about the detected location (like the coordinates). Let’s build a sample app that starts tracking the user’s position and displays the coordinates in the page. The structure of the project is the same we’ve already used in all the other samples: we’ll have a View (with a Button and a TextBlock) connected to a ViewModel, with a command (to start the detection) and a string property (to display the coordinates).

Please note: the purpose of the next sample is just to show you a scenario where handling the UI thread in the proper way is important. In a real project, using a platform specific API (in this case, the Geolocator one) in a ViewModel isn’t the best approach. We’ll learn more in the next post.

Here is how the ViewModel looks like:

public class MainViewModel: ViewModelBase

{

private readonly Geolocator _geolocator;

public MainViewModel()

{

_geolocator = new Geolocator();

_geolocator.DesiredAccuracy = PositionAccuracy.High;

_geolocator.MovementThreshold = 50;

}

private string _coordinates;

public string Coordinates

{

get { return _coordinates; }

set { Set(ref _coordinates, value); }

}

private RelayCommand _startGeolocationCommand;

public RelayCommand StartGeolocationCommand

{

get

{

if (_startGeolocationCommand == null)

{

_startGeolocationCommand = new RelayCommand(() =>

{

_geolocator.PositionChanged += _geolocator_PositionChanged;

});

}

return _startGeolocationCommand;

}

}

private void _geolocator_PositionChanged(Geolocator sender, PositionChangedEventArgs args)

{

Coordinates =

$"{args.Position.Coordinate.Point.Position.Latitude}, {args.Position.Coordinate.Point.Position.Longitude}";

}

}

When the ViewModel is created, we initialize the Geolocator class required to interact with the location services of the phone. Then, in the StartGeolocationCommand, we define an action that subscribes to the PositionChanged event of the Geolocator: from now on, the device will start detecting the location of the user and will trigger the event every time the position changes. In the event handler we set the Coordinates property with a string, which is the combination of the Latitude and Longitude properties returned by the handler.

The View is very simple: it’s just a Button (connected to the StartGeolocationCommand property) and a TextBlock (connected to the Message property).

<Page

x:Class="MVVMLight.Dispatcher.Views.MainPage"

xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation"

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml"

xmlns:local="using:MVVMLight.Dispatcher"

xmlns:d="http://schemas.microsoft.com/expression/blend/2008"

xmlns:mc="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/markup-compatibility/2006"

DataContext="{Binding Source={StaticResource Locator}, Path=Main}"

mc:Ignorable="d">

<Grid Background="{ThemeResource ApplicationPageBackgroundThemeBrush}">

<StackPanel HorizontalAlignment="Center"

VerticalAlignment="Center">

<Button Content="Start geolocalization" Command="{Binding Path=StartGeolocationCommand}" />

<TextBlock HorizontalAlignment="Center"

VerticalAlignment="Center"

Text="{Binding Path=Coordinates}" />

</StackPanel>

</Grid>

</Page>

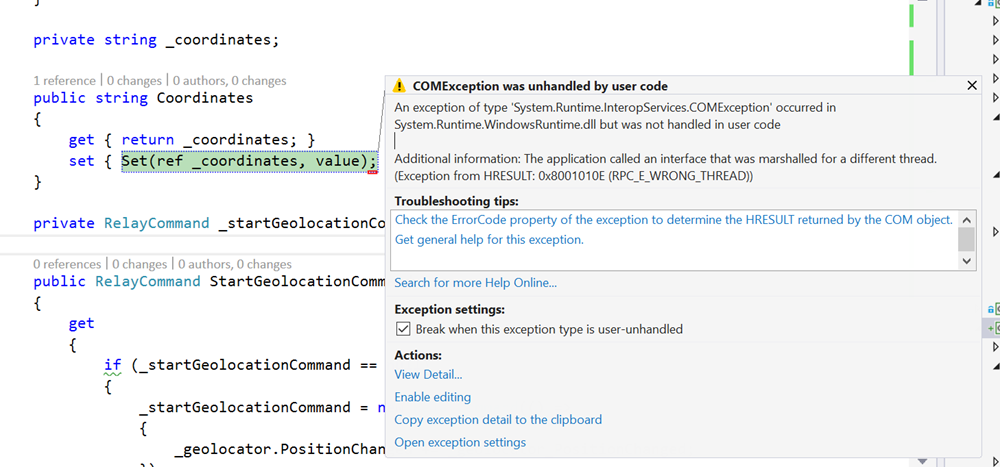

If we try the application and we press the button, we will notice that, after a few seconds, Visual Studio will show an error like this:

The reason is that, to keep the UI thread free, the event handler called PositionChanged is executed on a different thread than the UI one, which doesn’t have direct access to the UI one. Since the Coordinates property is connected using binding to a control in the page, as soon as we try to change its value we’ll get the exception displayed in the picture.

For these scenarios the Universal Windows Platform provides a class called Dispatcher, which is able to dispatch an operation on the UI thread, no matter which is the thread where it’s being executed. The problem is that, typically, this class can be accessed only from code-behind, making harder to use it from a ViewModel. Consequently, most of the MVVM toolkits provide a way to access to dispatcher also from a ViewModel. In MVVM Light, this way is represented by the DispatcherHelper class, which requires to be initialized when the app starts in the OnLaunched() method of the App class:

protected override void OnLaunched(LaunchActivatedEventArgs e)

{

Frame rootFrame = Window.Current.Content as Frame;

// Do not repeat app initialization when the Window already has content,

// just ensure that the window is active

if (rootFrame == null)

{

// Create a Frame to act as the navigation context and navigate to the first page

rootFrame = new Frame();

rootFrame.NavigationFailed += OnNavigationFailed;

DispatcherHelper.Initialize();

if (e.PreviousExecutionState == ApplicationExecutionState.Terminated)

{

//TODO: Load state from previously suspended application

}

// Place the frame in the current Window

Window.Current.Content = rootFrame;

}

if (rootFrame.Content == null)

{

// When the navigation stack isn't restored navigate to the first page,

// configuring the new page by passing required information as a navigation

// parameter

rootFrame.Navigate(typeof(Views.MainPage), e.Arguments);

}

// Ensure the current window is active

Window.Current.Activate();

}

DispatcherHelper is a static class, so you can directly call the Initialize() method without having to create a new instance. Now that it’s initialized, you can start using it in your ViewModels:

private async void _geolocator_PositionChanged(Geolocator sender, PositionChangedEventArgs args)

{

await DispatcherHelper.RunAsync(() =>

{

Coordinates =

$"{args.Position.Coordinate.Point.Position.Latitude}, {args.Position.Coordinate.Point.Position.Longitude}";

});

}

The code that needs to be executed in the UI thread is wrapped inside an Action, which is passed as parameter of the asynchronous method RunAsync(). To keep the UI thread as free as possible, it’s important to wrap inside this action only the code that actually needs to be executed on the UI thread and not other logic. For example, if we would have needed to perform some additional operations before setting the Coordinates property (like converting the coordinates in a civic address), we would have performed it outside the RunAsync() method.

In the next post

In the next and last post of the series we’re going to see some additional libraries and helpers that we can combine with MVVM Light to make our life easier when it comes to develop a Universal Windows app. In the meantime, as usual, you can play with the sample code used in this post that has been published on my GitHub repository at https://github.com/qmatteoq/UWP-MVVMSamples

Introduction to MVVM – The series

- Introduction

- The practice

- Dependency Injection

- Advanced scenarios

- Services, helpers and templates

- Design time data

Hi Matteo,

So one scenario I have is that a parameter is passed to a page to tell it what content to load.

Would you suggest passing this parameter as a message to the behind ViewModel? The other option I see is to keep an instance of the ViewModel in the View and call it directly, which is basically what I do now.

Ryan

Hello, using messages is indeed an option. Otherwise, you can get some help with other toolkits and libraries that integrate well with MVVM Light. For example, Template10 is a template for UWP apps which provides a base ViewModel class that gives you access to the OnNavigatedTo() method and to the navigation parameters. I’ve wrote about this here: http://blog.qmatteoq.com/template10-a-new-template-to-create-universal-windows-apps-mvvm/

Hi Matteo,

you advised against “using a platform specific API (in this case, the Geolocator one) in a ViewModel isn’t the best approach”

Please show me how to do it better, my app make use of the Geolocator class and PositionChanged event

Hello Christian,

sorry for the delay but I’ve been away for holiday and for business travels. The best solution, in this case, is to move all the platform specific code in an external class (like a service) and, by using dependency injection, leveraging only the interface in your ViewModel. This way, your ViewModel would do simply something like “_geolocatorService.GetPosition()”, but the real code that actually performs the operation will be stored in another class.