In the latest days I’ve started to work with Prism for Universal Windows apps and I’ve decided to share my experience with you. What is Prism? If you’re a long time Microsoft developer, you’ll probably already know it: it’s a very popular MVVM (Model-View-ViewModel) framework created by the Patterns & Practices division in Microsoft, with the goal to help developers to implement the MVVM pattern in their application and to support the most common scenarios.

Recently, the division has released a Prism version which is completely compatible with the Windows Runtime and, consequently, with Universal Windows apps development: the purpose of this series of blog posts is to see how to use it for this scenario and how it can help you developing a MVVM application.

I won’t discuss in details the advantages of using the MVVM pattern: I’ve already talked about this topic in the posts series about Caliburn Micro.

Prism vs the other toolkits and frameworks

How does Prism compare to the other popular MVVM toolkits and frameworks, like MVVM Light and Caliburn Micro? After playing a bit with it, I’ve reached the conclusion that it tries to take the best of the both worlds. Definitely, it’s much more similar to Caliburn Micro than MVVM Light: in fact, we’re talking about a framework, which offers many built-in classes and helpers that are useful to manage specific scenarios of the platform (like navigation, state management, etc.). Moreover, like Caliburn Micro, it uses some special classes that replace the native ones (like the App class or the Page class), which acts as a bootstrapper to properly setup all the infrastructure required by Prism to properly work.

However, one of the cons of Caliburn Micro is that it’s not ideal to developers that are working with MVVM for the first time: despite being very powerful, all the naming conventions tend to hide all the basic concepts behind the pattern, like the binding, the DataContext or the usage of the INotifyPropertyChanged interface. Prism, instead, except for some minor scenarios (we’ll see the details later) is still based on the standard MVVM fundamentals, so it uses concepts that should be familiar to every XAML developer like binding or commands.

The project setup

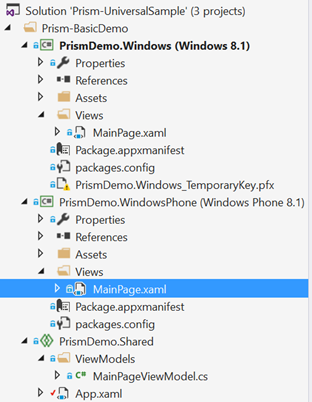

Let’s see how to create our first Universal Windows app using Prism: the first step is to create a new Universal Windows app project in Visual Studio, which will create the usual solution with a shared project, a Windows 8.1 one and a Windows Phone 8.1 one. If you’re familiar with Universal Windows app development, you’ll know that the shared project isn’t a real library, but it’s just a collection of shared resources (like classes, assets and XAML controls) which are linked to the two other projects. Consequently, you can’t add a reference to a third party library to the shared project: references are taken directly by the main platforms specific projects. The first step is, by using NuGet, to install both in the Windows and in the Windows Phone project the Prism.StoreApp library, which is the Prism version specific for Windows Store Apps.

The second step is optional, but highly recommended, since we’re going to use this approach in the next samples: when we talked about Caliburn Micro we’ve learned a bit more about dependency injection, which is a way to create objects at runtime instead of compile time. The pros of this approach is that we are able to easily change the implementation of a class (for example, because we want to swap a real class with a fake one that provides fake data at design time) without having to modify all the ViewModels that use it.

Also Prism supports dependency injection and it’s the best way to manage the dependencies of the ViewModels from other services of our application (like a navigation service, or a data service that retrieves our application’s data, etc.). The most widely used dependency injection’s container for Prism is Unity, which is also provided by the Pattern & Practices division by Microsoft: the next step, consequently, is to use again NuGet to install Unity in both project. It’s important to highlight that you’ll need to enable the option to extend the search also in pre-release packages: the latest stable version, in fact, doesn’t support yet Windows Phone 8.1, so you’ll get an installation error if you try to add it.

Convert the application into a Prism application

The first step to convert the Universal app into a Prism based app is to configure the bootstrapper: with this term, I mean the procedure that is required by the framework to properly initialize all the infrastructure required to work. In Universal Windows apps, the bootstrapper is the App class itself: we’re going to redefine the App class, so that it doesn’t inherit anymore from the native Application class, but from a Prism classed called MvvmAppBase.

To do this you need to follow two steps: the first one is to change the definition of the App class in the XAML, in the file App.xaml. You’ll need to add a new namespace, which is the one where the MvvmAppBase class is defined: the namespace is Microsoft.Practices.Prism.Mvvm. The second step is to replace the base Application tag with the MvvmAppBase one. Here is how the App.xaml file will look like at the end:

<mvvm:MvvmAppBase

x:Class="PrismDemo.App"

xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation"

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml"

xmlns:local="using:PrismDemo"

xmlns:mvvm="using:Microsoft.Practices.Prism.Mvvm">

</mvvm:MvvmAppBase>

The second step, instead, is to change the App class code, so you’ll need to edit the App.xaml.cs file: the first thing to do is to replace the class where the App object inherits from, which isn’t anymore Application but MvvmAppBase. Then, you’ll need to remove all the code and keep just the App constructor: Prism, in fact, offers its own way to manage the different application’s lifecycle events (like launched, activated, suspended, etc.).

Here is how a base App class for a Prism project looks like:

sealed partial class App : MvvmAppBase

{

public App()

{

this.InitializeComponent();

}

}

We’re not done yet in setting up the bootstrapper but, first, we need to create our first page, so that it will be easier to understand the next steps. As I’ve mentioned before, one of the advantages of Prism over Caliburn is that, despite being a powerful framework, it doesn’t hide all the basic MVVM infrastructure. However, there’s an exception: like in Caliburn, the connection between a View and a ViewModel is performed using a naming convention. You can use also another approach if you prefer (like using a ViewModelLocator or by directly binding the ViewModel as data context of the View), but the naming convention one is the easiest to use to take advantage of all the Prims features. The naming convention is very simple and it reminds the one used by Caliburn: you’ll have to place your ViewModels into a folder of your project called ViewModels, while the Views will be placed in a folder called Views. Since you’re working on a Universal Windows app, typically you’re going to create the ViewModels folder into the Shared project (since the ViewModels will be shared across the two platforms), while the Views folder will be created in the platform specific project, so that you can optimize the user interface for the two platforms.

There’s also another naming convention to follow, which is about the name of the files:

- The View should end with the Page suffix (like MainPage).

- The ViewModel should have the same name of the View, plus the ViewModel suffix (so, for example, the ViewModel connected to a page called MainPage will be named MainPageViewModel).

Now that you have created your first page of the application, you’re going to need to tell to Prism that it’s the default one, that needs to be loaded when the application starts. You’re going to achieve this goal by overriding in the App class one of the methods offered by the MvvmAppBase class, which is OnLaunchApplicationAsync(). Here is how it looks like in a typical Universal Windows app:

protected override Task OnLaunchApplicationAsync(LaunchActivatedEventArgs args)

{

NavigationService.Navigate("Main", null);

return Task.FromResult<object>(null);

}

The method uses one of the built in helpers offered by Prism, that we’ll cover in details in the next posts: it’s a class called NavigationService, which is used to perform navigation from one page to another. To navigate to another page you need to use the Navigate() method, which accepts as first parameter the name of the page, which is the name of the View without the Page suffix: in the previous sample, by passing as parameter the value Main we’re assuming that, in the Views folder of our project, we have a page called MainPage.xaml. For the moment, ignore the second parameter, which is simply set to null: it’s the optional parameter that we can pass to the destination page.

The last line of code executed by the operation is a “workaround”: as you can see, the OnLaunchApplicationAsync() method returns a Task, so that you can perform asynchronous operations inside it. Since, in this case, we’re not performing any of them, we’re returning a “fake” one by using the Task.FromResult() method and passing null as parameter.

Setting up the dependency injection

The last step before starting working for real on the application is to configure the dependency injection container: as already mentioned, we’re going to use Unity. The container initialization is made in a method offered by the MvvmAppBase called OnInitializeAsync(), which is executed when the application is initialized for the first time. The approach here is the same we’ve seen in Caliburn: we are able to register own services, so that they will be automatically injected in the ViewModels when we’re going to use them. However, we have also to register some of the built-in services, so that we can use them in the other ViewModels: they are the NavigationService (which we’ve already seen and it’s used to perform navigation from one page to the other) and the SessionStateService, which we’ll see in details in another post. For the moment, it’s important just to know that it’s a helper to make it easier for developer to manage the suspension and termination of the app.

If you have some experience with Caliburn or MVVM Light, you’ll know that one of the required step to properly set up the dependency injection is to register, inside the container (which is the class that takes care of dispatching the objects when required), all the ViewModels of the project. With Prism this is not required: thanks to the naming convention previously described, in fact, we are able to tell to Prism (using a class called ViewModelLocatorProvider) that we want to automatically register every available ViewModel.

Here is how the complete App.xaml.cs looks like:

sealed partial class App : MvvmAppBase

{

IUnityContainer _container = new UnityContainer();

public App()

{

this.InitializeComponent();

}

protected override Task OnLaunchApplicationAsync(LaunchActivatedEventArgs args)

{

NavigationService.Navigate("Main", null);

return Task.FromResult<object>(null);

}

protected override Task OnInitializeAsync(IActivatedEventArgs args)

{

// Register MvvmAppBase services with the container so that view models can take dependencies on them

_container.RegisterInstance<ISessionStateService>(SessionStateService);

_container.RegisterInstance<INavigationService>(NavigationService);

// Register any app specific types with the container

// Set a factory for the ViewModelLocator to use the container to construct view models so their

// dependencies get injected by the container

ViewModelLocationProvider.SetDefaultViewModelFactory((viewModelType) => _container.Resolve(viewModelType));

return Task.FromResult<object>(null);

}

}

In the previous code you can see the three required steps to setup the dependency injection:

- We create a property which type is IUnityContainer and we create a new instance.

- We register, by using the RegisterInstance<T>(), the previously described SessionStateService and NavigationService.

- By using the SetDefaultViewModelFactory() method of the ViewModelLocationProvider class, we are able to automatically register every ViewModel we have in our project, so that it can be automatically connected to the View when required..Now we have defined the proper infrastructure required by Prism: there’s only one last step to, which is to tell to every View in our application which ViewModel to use. We achieve this by adding, in the Page class in the XAML, a property offered by Prism called AutoWireViewModel, which is offered by the ViewModelLocator class: by setting it to True, we enable the naming convention, so the View will automatically look for its own ViewModel and will assign it as DataContext. Here is how a page in a Prism application looks like:

<Page x:Class="PrismDemo.Views.MainPage" xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation" xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml" xmlns:local="using:PrismDemo.Views" xmlns:d="http://schemas.microsoft.com/expression/blend/2008" xmlns:mc="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/markup-compatibility/2006" xmlns:mvvm="using:Microsoft.Practices.Prism.Mvvm" mc:Ignorable="d" mvvm:ViewModelLocator.AutoWireViewModel="True" </Page>Wrapping up

So far, we’ve just seen how Prism works and how to setup the project. In the next post, we’re going to start creating the application for real, by seeing how to use binding and how to define commands to manage the user interaction. If you want a sneak peak of a real project, you can find the sample we’re going to use in the next post on GitHub at the URL https://github.com/qmatteoq/Prism-UniversalSample

Index of the posts about Prism and Universal Windows app

- The basic concepts

- Binding and commands

- Advanced commands

- Navigation

- Managing the application’s lifecycle

- Messages

- Layout management

Sample project: https://github.com/qmatteoq/Prism-UniversalSample

Thanks for posting. Very clear time-saving post.

You’re welcome!

Found one thing missing, looks like MainPage need to be inherited from VisualStateAwarePage, otherwise code doesn’t compile. Good think you have in git.

Thanks for the hint!

Haven’t read the entire post yet, but looking good! Thanks for sharing, by all means 🙂

So Great!!! 🙂